The church had to go a long way until in Luther’s theologia crucis she gained the full understanding of the cross of Christ. It has often been observed how small a role the cross plays in the theology of the Ancient Church. To be sure, the church of the first centuries as well as the church throughout the ages has lived by the death of Christ and has known that. Every Lord’s Day, every celebration of the Eucharist, made the death of the Lord a present reality. There has never been another Eucharist. Hardly another passage of the Old Testament is quoted by the Fathers as often as Isaiah 53. The sign of the cross was already in the second century an established Christian custom. Christian art of the time, however, represents our redemption by showing the types of the Old Testament, not the scenes of the passion of Christ. Not till the fourth century, and then only hesitantly, does Christian sculpture begin to represent the narrative of the passion as one of the many gospel stories. And theology is not able to say very much of the death of Christ either. As soon as the great question is put: Cur Deus homo? [Why did God become man?] it is understood as a question for the rationale of the incarnation rather than of the death of Christ. The doctrine of the cross (not yet understood as a doctrine in its own right) is contained in the doctrine of incarnation. It is also contained in the mystery of the resurrection, since what we call Good Friday and Easter were celebrated by the oldest church simultaneously in the festival of “pascha.” The actual event of our salvation is the incarnation: “On account of His infinite love He became what we are, in order that we might become what He is” (Irenaeus, adv. haer, V praef). And the beginning of our redemption, of our rising from the dead, is His resurrection.

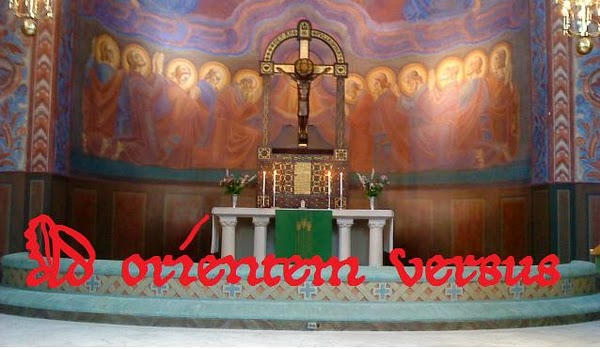

The church had to go a long way until in Luther’s theologia crucis she gained the full understanding of the cross of Christ. It has often been observed how small a role the cross plays in the theology of the Ancient Church. To be sure, the church of the first centuries as well as the church throughout the ages has lived by the death of Christ and has known that. Every Lord’s Day, every celebration of the Eucharist, made the death of the Lord a present reality. There has never been another Eucharist. Hardly another passage of the Old Testament is quoted by the Fathers as often as Isaiah 53. The sign of the cross was already in the second century an established Christian custom. Christian art of the time, however, represents our redemption by showing the types of the Old Testament, not the scenes of the passion of Christ. Not till the fourth century, and then only hesitantly, does Christian sculpture begin to represent the narrative of the passion as one of the many gospel stories. And theology is not able to say very much of the death of Christ either. As soon as the great question is put: Cur Deus homo? [Why did God become man?] it is understood as a question for the rationale of the incarnation rather than of the death of Christ. The doctrine of the cross (not yet understood as a doctrine in its own right) is contained in the doctrine of incarnation. It is also contained in the mystery of the resurrection, since what we call Good Friday and Easter were celebrated by the oldest church simultaneously in the festival of “pascha.” The actual event of our salvation is the incarnation: “On account of His infinite love He became what we are, in order that we might become what He is” (Irenaeus, adv. haer, V praef). And the beginning of our redemption, of our rising from the dead, is His resurrection.Thus for the Ancient Church, as even today for the Eastern Church, the cross is hidden in the miracle of Christmas and in the miracle of Easter. The darkness of Good Friday vanishes in the splendour of these festivals. The cross is outshone by the divine glory of Christ Incarnate and the Risen Lord. Even for a long time after the church begins to represent Christ Crucified in its art, the glory outshines the cross. When at the end of the Ancient World and in the early Middle Ages Christ Crucified takes the place of Christos Pantokrator, in the triumphal arch of the church above the altar. He is still shown as king triumphant. The Christ of the Ancient Church and the Christ of the Romanesque churches of the Middle Ages does not suffer. He remains triumphant, even on the cross. And the cross, too, appears always as a sign of victory rather than of suffering and death: “In hoc signo vinces,” “Vexilla regis prodeunt fulget crucis mysterium.” [“By this sign you will conquer.” “The royal banners forward go [and] the mystery of the cross shines forth.”]

Why is that so? How is that limitation of Ancient Christianity and its theology to be explained? Certainly it must not be forgotten that the divine revelation given in Holy Scriptures is so rich that whole centuries are necessary to understand its content fully. It cannot be expected that the Church of the First Ecumenical Councils should already have solved the problems of the medieval Western World. But even the selection of problems to deal with was determined by the horizon of the Fathers’ life and thought. The Greek would have considered it bad taste to represent the scene of the crucifixion. Would you hang a painting showing a criminal on the gallows in your dining room? As to the meaning of redemption, the Greek Fathers could not get away from the idealistic conception of man. Even the great Athanasius [ca. 293-373] never considered, “quanti ponderis sit peccatum.” [“how great is the weight of sin”] They all are Pelagians. For them, as for Dostoevski [1821-1881] and the whole of Russian orthodoxy, the sinner is basically a poor sick person who is to be healed by patient love and heavenly medicine, not, as for the Romans, a criminal, an offender of the law who needed discipline and justification. But how can I understand the cross, if I do not know by whom and by what Christ was brought to the cross?

I caused Thy grief and trembling;

My sins, in sum resembling

The sand-grains by the sea,

Thy soul with sorrow cumbered,

And raised those woes unnumbered

Which press in dark array on Thee.

The lack of full understanding of the greatness of sin is the reason why the Ancient Church and the Church of the East never reached a theologia crucis.

Herman Sasse, Letters to Lutheran Pastors 18

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar